Recently, doctors have developed a “brain-healthy” diet that appears to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease by as much as 53 per cent. There is even a bonus; you can follow the diet in moderation and still benefit from its effects.

Recently, doctors have developed a “brain-healthy” diet that appears to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease by as much as 53 per cent. There is even a bonus; you can follow the diet in moderation and still benefit from its effects.

This new eating plan is called the MIND Diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) and it borrows elements from the heart-healthy Mediterranean Diet and the blood pressure-lowering DASH Diet (which stands for Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension). All three diets are essentially plant-based and low in high-fat foods. But the MIND Diet places a specific focus on foods and nutrients linked to optimal brain health, including berries and green leafy vegetables.

The study, developed by researchers at Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center, aimed to better understand how nutrition could improve brain health and lessen the cognitive decline and memory deterioration that comes with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. “Past studies have yielded evidence that suggests that what we eat may play a significant role in determining who gets Alzheimer’s disease and who doesn’t,” says Rush Nutritional Epidemiologist Martha Clare Morris.

According to the study, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association,

researchers collected data on the food intake of 923 Chicago-residents between the ages of 58 and 98. The participants’ eating habits were tracked on how closely they followed one of three diet plans: the MIND Diet, the Mediterranean Diet, or the DASH Diet.

The results revealed that strict adherence to any of the three diets lessened the chances of getting Alzheimer’s. The risk of decline for participants following the MIND Diet was a 53 per cent decrease, while those following the Mediterranean Diet experienced a drop of 54 per cent, and individuals under DASH saw a 39 per cent

decline in risk.

“One of the more exciting things about this [study] is that people who adhered even moderately to the MIND Diet had a reduction in their risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Morris. “I think that will motivate people.”

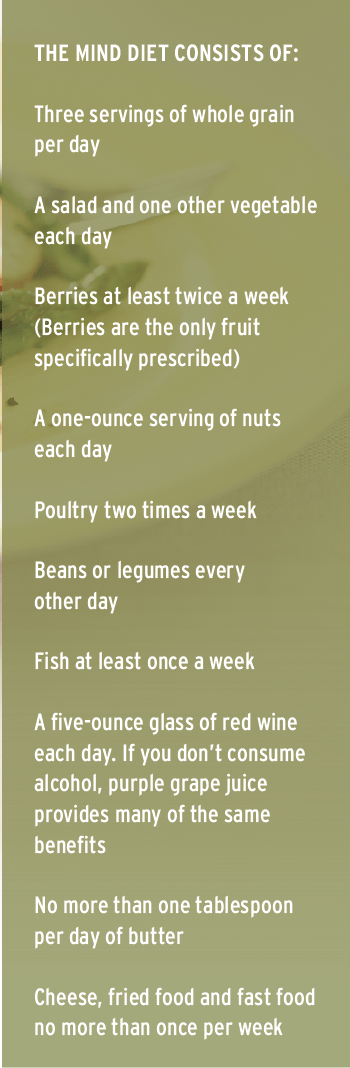

The MIND Diet consists of 15 dietary components, including 10 “brain-healthy food groups” and five “unhealthy-brain” food groups. The healthy groups include berries, green leafy vegetables as well as other vegetables, whole grains, nuts, beans, fish, poultry, olive oil and wine. The unhealthy groups are red meats, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried or fast food.

What’s more interesting is that the MIND Diet is easier to follow than the Mediterranean Diet, which calls for daily consumption of fish and three to four servings of both fruits and vegetables, Morris says. And where the Mediterranean and DASH diet plans promote fruit intake in general, berries are the only recommended fruit as part of the MIND Diet. “Blueberries are one of the more potent foods in terms of protecting the brain,“ says Morris, and strawberries have also performed well in past studies examining the effects of food on cognitive function.

These new discoveries also suggest that the protection against Alzheimer’s disease is greater for those participants that adhere to the MIND Diet for longer periods of time. As is the case with many health-related habits, including physical exercise, Morris says, “You’ll be healthier if you’ve been doing the right thing for a long time.”

The results of the MIND Diet study indicate strong preliminary evidence that brain-boosting benefits can be found in food intake and diet regimens. More importantly, we now have clear evidence of the fact that the early adoption of new “brain healthy” eating habits, even in moderation, can boost brain and lessen the risks of cognitive decline.

What If You Did More Than Just Change Your Diet?

While the MIND Diet has unveiled significant results when it comes to an individual’s diet, what’s stopping us from taking these benefits even further and seeing what would happen when a “brain healthy” diet is enhanced with a series of lifestyle modifications? The FINGER Study (derived from Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability) reveals that beneficial results can be reached when not just one, but multiple factors like diet and exercise, are targeted.

This Swedish study, looked at multiple approaches to improving and maintaining cognitive functioning through lifestyle interventions based on the objective of lowering the risk of dementia.

Led by Miia Kivipelto, professor of Clinical Geriatric Epidemiology at Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, the FINGER Study followed 1,260 participants who were at a high risk of developing dementia. After being randomly assigned into two groups, the first group, which was also the control group, received the best medical advice available and regular cognitive testing. The second group was subject to an intensive series of lifestyle interventions including diet, exercise, cognitive training and social activity.

The intervention was delivered in four components:

- Diet: this was administered by nutritionists in individual and group sessions, and included individual tailoring of the participants’ diet.

- Exercise: this was administered by physiotherapists following international guidelines and included exercises to build muscle strength and aerobic activities.

- Cognitive stimulation: this was administered by psychologists in group and individual sessions. It included a web-based training program delivered in short sessions, three times per week for two six-month periods, and education on cognitive changes in older people. Frequent discussion meetings encouraged social interaction within the intervention groups.

- Metabolic and vascular risk management: these risk factors were actively managed with frequent meetings and assessments by the study nurse and physician to take blood pressure and other measurements relevant to vascular health. After each assessment, participants were given advice on lifestyle management and advised to consult their own doctors if necessary, but were not directly prescribed medication.

The results from the study demonstrated significant improvements on a comprehensive cognitive examination. In addition to performing better overall, the intervention group improved on memory tests, executive function (such as planning, judgment, and problem-solving), and speed of cognitive processing.

“This is the first randomized control trial showing that it is possible to prevent cognitive decline using a multi-domain intervention among older at-risk individuals,” says Kivipelto. “There are links between cognitive decline in older people and factors such as diet, heart health, and fitness. Our study shows that an intensive program aimed at addressing these risk factors might be able to prevent cognitive decline in elderly people who are at risk of dementia.”

An extended, seven-year follow up investigation to the FINGER Study is now planned. It will include the measuring of dementia and Alzheimer’s incidence, giving further life to the idea that mental deterioration can be significantly reduced by targeting multiple lifestyles factors.